- Home

- Ged Gillmore

Cats on the Run Page 9

Cats on the Run Read online

Page 9

Ginger looked along the road, but the first trees of the forest were still quite a distance away. She’d never make it to them in time, even if she wasn’t so tired. She hadn’t passed any shelter on the way up the road either, and the hedgerow wasn’t nearly thick enough to provide protection. Raindrops would drip deeply and drop damply down it and drench her. Drat! She looked towards the sunset, into the stubbly field that ran away from the road, but it was empty. What to do? Where else could she go? What do you think, dear reader? What should she do?

Turn around, Ginger darling. Look east! No, sweetheart, the other way. There we go. Ginger turned and looked at the grassy field beneath the ominous sky, its further reaches no longer green but already in dark shadow as the night and the storm rolled in. Halfway across it, no more than twenty metres away, sat an old pigsty. Without a second thought Ginger ran to it. Now, when cats walk through grass they step gingerly, as we know. Even if they’re not ginger or Ginger, but if they are ginger and Ginger, they step very gingerly indeed. But when they run through grass it’s a different story. They’re low to the ground, flat, and fast. Or fat and fast in Ginger’s case, but there’s no need to get personal. Anyway, Ginger ran all the way to the pigsty. This was further than she’d run in quite a while, and when she arrived she was out of breath. She sat there with her mouth open and watched as the first fat drops of rain fell from the sky.

Suddenly there was a huge crack of thunder, KERBOOM! and the pigsty shook around her. Then it stopped shaking, but something beside her carried on moving. Something big. Ginger turned her head slowly but saw nothing but a few wooden planks nailed to the posts that held up the pigsty’s roof. Straw was poking out from between the planks, and as she watched, the something big moved again on the other side of the wood. Ginger looked out at the rain, halfway to torrential already. She summoned up her courage, coughed slightly, and said, ‘Hello?’ There was no response, but the something big moved again, and she heard what sounded like a sneeze. ‘Oh,’ she thought. ‘This is ridiculous’, and she jumped up on top of the little wooden wall to see what was on the other side.

‘Goodness!’ she said out loud when she got up there. ‘Pigs!’

She wasn’t wrong. There stood two huge pigs, snuffling around in the straw and quite positively not looking at her.

‘“Pigs,”’ said one pig to the other. ‘“Pigs”, she says. Like she was expecting to find a crocodile in a pigsty.’

‘I’m sorry,’ said Ginger. ‘I thought this place was abandoned.’

‘Really!’ said the pig who had spoken first, the one closer to her. ‘How very dare you! We had it decorated only last year.’

‘Don’t lower yourself, Beryl,’ said the other pig. ‘She looks like a stray and probably just wants some money.’

‘Good luck with those bellies!’ said the pig called Beryl. ‘She’d struggle to raise a few pennies at a pension fund.’

I don’t know about you, but I have no idea whatsoever what that means and nor did Ginger, but the two pigs found it very funny and chortled away at Ginger’s expense.

Now, of course if you or I found two snobby pigs laughing at our bellies or our fundraising abilities, we’d be most upset. It’s a strange rule of human life that you may not like someone, but you still want them to like you. But cats aren’t like that, you see. Not if they’re high up. If they’re down on the ground or lying on the bed or even on the back of the sofa, oh yes—they want to be fussed! They want to be stroked and admired and told how cute and lovely they are. But any higher than waist height and they couldn’t give a flying fox what you think of them. Pah, they can hardly even hear it.

So Ginger sat up on the wooden fence that ran around the pigsty and licked her chest while the rain hammered down on the corrugated iron overhead. Have you heard the noise rain makes on corrugated iron? It’s loud! So loud that if you’d been there when I was telling you this story you wouldn’t have even heard it. What? What did she find in the pigsty? A what? Who’s Beryl? That kind of thing.

Fortunately, Ginger didn’t mind the noise. She was just glad to be out of the horrible rain. She sat there, washing herself slowly, glancing occasionally at the two fat pigs and wondering what they were laughing about. Outside the sty, the grassy field turned slowly to mud, and soon the huge raindrops threw up big brown splashes when they landed. Then it grew even darker, and even with her cat’s eyes Ginger struggled to see until suddenly the whole landscape was lit up in a flash of silver lightning. One thousand, two thousand, three thousand, KERBOOOOOOM, the thunder rolled in, and once more the pigsty shook so hard that Ginger nearly fell off the wooden fence. ‘Mmm,’ she thought. Maybe it wasn’t such a good idea to sleep up there after all. So she jumped down to the straw on the non-pig side of the planks and was just getting settled again when she saw a movement in the corner of her eye.

A rat! Ginger didn’t even think, she just did a quick sideways movement towards it. But before she was even halfway to it, the rat made a horrible squealing noise. There was another great flash of lightning, and Ginger saw, to her disbelief and confusion, the rat dead on the floor in front of her, its neck open and shining red until the lightning ended and all was black again. Oo-er missus. Ginger didn’t like the look of that. She was hungry alright, but whatever had killed that rat was dangerous, and what’s worse, it was a lot faster than she was. She backed up towards the fence and sat wondering what to do. When the lightning flashed again, the rat was gone.

The rain was falling on the city too that night, but in the Burringos’ apartment you could hardly hear it. Occasionally the wind would change direction and smatter it against the windows, but otherwise all was quiet. Rodney and Janice had gone out for an Indian meal (the Singh children from two streets down) and left Major all alone. They’d fed him before they’d left and even given him a saucer of milk, and now he sat on the warm, dry windowsill, thinking life was good.

Half an hour later he was still sitting there and thinking life was kind of nice. And another half an hour after that, he was sitting there as bored as bat’s bits. Where were the mice darting across his stable floor? Where was the wind bending the trees overhead and scattering the courtyard with brittle debris? Where were the bats that used to dart in through the farmhouse window and tell him all the gossip from the countryside? He’d thought he needed a change and maybe he did, but not to this sterile apartment where nothing ever happened, with owners who slept all day and then went out at night. It was rubbish.

‘Right,’ Major thought. ‘I’m outta here. Like a cat outta hell.’ And he went and sat next to the apartment door, waiting for the Burringos to arrive home so he could say, ‘See ya, wouldn’t want to be ya’, and head off home.

Well, I don’t know about you, dear reader, but I see a slight conflict of values approaching, don’t you? Don’t you? Oh, you were kidding. Tch, you! Uh-oh, here it comes. It was two o’clock in the morning when Rodney and Janice stumbled home. They’d had a little too much to eat—having found themselves unsatisfied by the Singh children, they’d eaten the kids’ Poppa(dom) and Ma(sala) too—and they’d had much too much to drink. Janice had a particular fondness for cherry brandy, which wasn’t a fondness that the liqueur returned. It made her loud and not a little obnoxious when, as we know, she was normally so sweet and charming.

‘Ooooh,’ she said when she eventually managed to open the door to the apartment. ‘Look who’s ’ere to say ’ello. ’Ello, gingey puddy wuddy cat.’

Janice breathed cherry fumes all over Major, who was already a little grumpy at having to wait so long for her and Rodney to come home. He gave her his most withering stare, flicked his tail slightly, and walked between her legs and out of the apartment.

‘’Ere, where’s ’e going?’ said Janice, who always dropped her h’s when she was drunk.

‘Who?’ said Rodney, h’s fully intact. He hadn’t seen that Major had sauntered between his legs too as he stumbled behind Janice into the apartment.

‘’Im! That

fat ginger substitute—grab ’im!’ screamed Janice.

Major thought that was rich. He was certainly broad-shouldered, but he’d never been fat in his life. ‘Now listen here, wart-face,’ he said. But that was all he got to say before Rodney turned, picked him up, and threw him back into the apartment.

‘Do you mind!’ said Major, in a serious grump now, and running back to the door. This time Janice grabbed him and gave him a smack on his haunch with the palm of her hand. Ouch! Can you imagine how painful it is for a cat to be hit by something as big as a witch? That would be like a huge giant slapping you across the ribs with a hand as big as a car. Ouch, ow, ow. Well, as you can imagine, Major wasn’t going to take that without protest.

‘Eeeeeeeowwwwwooooh!’ screamed Janice. ‘’E bit me! The miserable little doormat bit me!’

And she threw Major across the room. He landed on the kitchen table and was still steadying himself from the shock when he saw Rodney coming towards him, a distinctive tinge of green rising in his cheeks. Rodney had grabbed a broomstick which had been leaning against the living room wall, and now as he approached he raised it high above his head, narrowly missing the lampshade and even more narrowly missing Major as he slammed the twiggy end down on the table. KERBANK!

Major only just got out of the way in time—otherwise he would have been flat cat. He jumped down to the floor and crawled under the sofa, but within a second Rodney and Janice were on their knees, poking him out. Rodney was using the handle of the broomstick, and Janice was using a tennis racquet, which she had just magicked into existence.

‘Get lost!’ growled Major. ‘Leave me alone!’ Well, eventually they did, but only because it was all too much effort for Janice, and she was worried her cherry brandy and huge Indian meal might come up again.

‘Fuhgeddaboudit,’ she said to Rodney. ‘Stupid blooming moggie. Let’s go to bed.’

‘Already?’ said Rodney. ‘It’s not even light yet. Go on, let’s skin him.’

‘Nah,’ said Janet. ‘I’m cream-crackered. And besides, we need to keep ’im alive till we get the other one for the experiment. Oops.’

She put her hand over her mouth. Not because she’d done a big cherry brandy and Indian children burp but because Rodney had shot her a withering look. They weren’t supposed to talk about the experiment in front of the cat.

‘Yes,’ said Rodney deliberately. ‘Let’s go to bed.’

An hour later the house was quiet again but for the sonorous sounds of sorcerers’ snoring. Major dragged himself out from under the sofa and licked himself back into shape. ‘Rattlesnakes,’ he thought to himself. ‘This place is seriously uncool. I have got to get me out of here.’ He went and sniffed at the front door again, then had a good old scratch at the carpet to check the tunnelling options, which proved themselves clearly not-gonna-happen. He checked all the windows and even tapped the walls for weak points. Na-huh. He climbed the stairs and crept past the reverberating secret-upstairs-locked room door. No luck there either. The spare bedroom had a huge dent in the wall from an argument where Janice had thrown a Wedgwood statuette at Rodney, but it was no help. The flat was hermetically sealed.

‘Oh dear,’ said Major. For the first time it dawned on him that he was in serious trouble.

A BIT OF A SURPRISE

Well, where would you rather be right now? Locked in a hermetically sealed apartment with two witches whose only reason for not skinning you is that they want to put your brain into another body? Or stuck in a pigsty in the middle of a rainstorm with a mysterious rat-murdering monster? Now, this may be an everyday dilemma for you. Maybe this is one of those decisions where you’d have to think for, hmm, thirty seconds and then make up your mind. If so, bully for you. Me, I ain’t so sure. Ginger, I can tell you, would have gone for the apartment option just then. Things had got a little hairier since we last saw her, you see. The pigs were not helping. She’d tried jumping in with them, thinking whatever huge carnivorous beast was out in the dark would surely go for bacon over cat gut, if only from the point of view of quantity over quality.

‘Get your furry frame out of my straw!’ said the pig whose name she didn’t know as soon as she saw her.

‘You tell her, Mildred,’ said the other one, which at least sorted out the name problem.

‘I mean it,’ said Mildred. ‘You scram now or I’m going to bite you.’ And she bared her horrible piggy-yellow teeth. Now, if you know anything about pigs, you probably know this, but just in case you don’t I’m going to tell you. Pigs bite! And when they bite they don’t stop until they can feel their teeth crunching against each other.

‘But there’s a big carnivorous monster out there,’ said Ginger. ‘You can’t send me back out there.’

‘You mind your cheek, young lady,’ said Mildred, taking a step forwards. ‘I mean it, I’ll bite.’

Well, seeing as you’re so good with these decisions, why don’t you decide? Stay in the pen with the teeth-baring pigs or expose yourself to a huge carnivorous rat-killing monster? Huh? Well, unfortunately, you weren’t there for Ginger to consult, otherwise I’m sure she’d have taken notes and considered your feedback. Instead she spat somewhat disrespectfully at Mildred in that way that cats do sometimes and jumped back up onto the wooden fence that ran around the pen. Behind her she heard Mildred say, ‘You see, Beryl, you have to take a firm trotter with these cats. It’s the only language they understand.’

‘Mmm,’ said Beryl. ‘Scroffle scroffle oink oink.’

Ginger ignored them. Instead she stared down at the straw on the other side of the enclosure, sodden with muddy raindrops. There lay another four rats, all dead and looking somewhat surprised. And out in the dark of the wild wet night, she saw two huge green eyes. And then, as she watched in terror, she saw some brilliant white teeth appear below them. The teeth moved slowly apart, and a pinky-pink tongue flicked between them as the teeth’s owner said, ‘Surprise!’ And with that a very muddy, very wet, and very happy-looking Tuck jumped in out of the rain.

‘Hiya!’ he said. ‘Did I surprise you? Did I? Look at all the mice I got. How are you? What’s in there? Is it pigs?’

Well, I struggle to describe all the emotions that ran through Ginger at that moment. She was firstly furious at her feline friend for frightening the flipping fur off her. Secondly, she was surprisingly serene at the serendipitous sensation of seeing him again. Thirdly, she was hungry. Mighty, mighty hungry.

‘Oh,’ she said. ‘I was wondering when you’d turn up. Do you want me to sashimi these for you while you freshen up?’

‘Ooh, yes please,’ said Tuck. ‘I might just have a little shower before dinner. You should do it too. You know how dirty pigs are.’

‘Well, really!’ Ginger heard Beryl say. ‘How rude!’

‘Disgusting,’ said Mildred in return. ‘I really cannot wallow in these conditions.’

But Tuck didn’t hear them. He was outside again, singing in the rain.

‘Pigs are dirty,

Girls are flirty,

I once had a little friend called Bertie.

Bertie ate a spoon,

He died too soon,

They put him in a rocket ship and sent him to the moon.’

‘That doesn’t even make sense,’ thought Ginger as she sliced up the rats, but she didn’t mind. She was too relieved that she was about to eat and not be eaten, and truth be told, not a little curious about how Tuck had turned up in the night.

‘Well,’ said Tuck as he licked the last of the rat’s tail off his lips. ‘It was all feline fine at first. I felt funny in my tummy when you said goodbye, but then the barn cats woke up and we played I spy, which is this really complicated and difficult game. Then we slept again, which was exhausting. Then, when we woke up, we got talking about ambitions, and I said I wanted to find the mushroom sauce, and they said what do you mean, and I said how we’d come to the moon to look for mushroom sauce and—’ Tuck paused and to Ginger’s huge surprise she saw he was crying. ‘And �

� and … and …’ He was sobbing so hard he could hardly talk.

‘Do keep it down, you foul moggies!’ said Mildred.

‘Oh shush, Mildred,’ said Beryl. ‘Can’t you see the little thing’s upset?’

I can’t tell you the look that Mildred gave Beryl at this point because they’re inside the wooden pen and the action’s happening on the outside, but I’m guessing it wasn’t pretty.

‘Oh dear,’ said Ginger. ‘What did they say?’

‘Waaah!’ said Tuck. ‘They said we weren’t on the moon and that even if we were, it wouldn’t matter because the moon wasn’t—sniff—waahhh … they said it wasn’t even made of mushroom sau-or-oor-oooorce.’

‘What did he say about the moon?’ said Mildred.

‘See?’ said Beryl. ‘You’re interested too now.’

‘Everything’s a competition with you, isn’t it, Beryl,’ said Mildred, and the two pigs got into a real oink-off so that for a while they didn’t hear a word the cats were saying.

‘It’s not true, is it?’ said Tuck, wiping his nose on his paw and looking over it at Ginger. ‘We are on the moon, aren’t we?’

‘Well … ,’ said Ginger. ‘Strictly speaking …’

‘Waaaah,’ said Tuck. ‘Waaah. … Even if we weren’t on the moon I’d want you to pretend we were just so I don’t feel this bad. And even if it wasn’t made of mushroom sauce I’d want to believe it was so I could look forward to having lots and lots of it until I couldn’t eat any more.’

‘Are you sure?’ said Ginger.

Tuck nodded slowly. He was gulping and snotty and too upset to say anything else.

‘Well then,’ said Ginger. ‘That’s easy. Yes, we are on the moon. And yes, it is made of mushroom sauce. We just need to find a lake or some other surface where the moon’s crust is shallow enough for sauce to still be sitting.’

‘Really?’ said Tuck, his eyes flashing green with pleasure. ‘Is it really true? Really?’

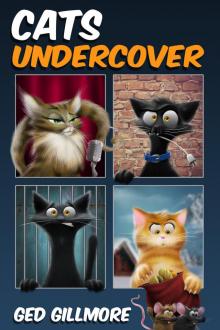

Cats Undercover

Cats Undercover Cats on the Run

Cats on the Run Cats On The Run (Tuck & Ginger Book 1)

Cats On The Run (Tuck & Ginger Book 1)