- Home

- Ged Gillmore

Cats on the Run

Cats on the Run Read online

CATS ON

THE RUN!

by

GED GILLMORE

WARNING!

This is the story of some cats I know and the frankly horrible things that happened to them last year. How they got what they thought they wanted, and how it nearly killed them. But before I begin the story, I need to confirm you’re up to hearing the ghastly events it contains. Are you tough enough? Are you rough enough? Are you downright gruff enough? If not, I recommend you put this book down right now and go back to your colouring-in, you big baby. Continue only if you are up for a Big Action Drama (B.A.D.) book. It’s rough, tough, and ain’t got no fluff. Are you down with that? Are you up for it? Have you looked left and right? OK, here we go.

THE FIRST BIT

Once upon a time there were two cats, and their names were Tuck and Ginger. Ginger was a ginger cat (surprise!); she had thick, striped fur; six bellies; and could say ‘miaow’ in seven languages. She’d been around the block a few times, Ginger had, and she didn’t mind telling you about it. For example, you might be picking your nose when you thought no one was looking, and Ginger, appearing from nowhere, would tell you about a boy she once knew in New York who picked his nose so hard his brain came out on the end of his finger.

Or you might say you’d just got back from Tibet. ‘Pah!’ Ginger would say. ‘Tibet! It’s all cheap sheep and chirpy Sherpas.’ She was so well travelled, you see, so experienced, so been-there-done-that, that not a lot impressed her. Not that Ginger showed off. Oh baloney, no. She didn’t think she was superior for having had such a varied and—as you’ll learn—hard life. But she didn’t hide it either. Ginger didn’t often go skydiving these days, but everyone knew she could do it.

Now, Tuck couldn’t be any more different. This, as you’ll find out, is both a good and a bad thing. Most things are both good and bad, have you noticed that? What’s the nastiest thing in the world, for example? Personally, I’d say poo is probably the most horrible thing in the world. But, hey, if there was no poo then all the food you’d ever eaten would still be inside your body, sitting there, gassy and rotting, and washing about your insides. You’d look like a politician!

Anyhoo, Tuck was a very different cat from Ginger. Firstly, he was born in a refugee camp, which has no direct bearing on this story but is interesting because it was a refugee camp built for dogs. Tuck grew up in a little cage in the cat room, which the camp management had been forced to set up for the cat refugees who kept arriving. For the first year of his life Tuck knew nothing of the outside world. All he heard—morning, noon, and night—was the howling of abandoned dogs. Is there a lonelier or sadder sound in the world? (Here’s a clue: no.)

Now, whether it was this strange upbringing that sent Tuck slightly loop-the-loop or some other factor, we will never know. The point is that Tuck was a little, how shall I put it? Well, you decide: Tuck was the kind of cat who would interrupt a conversation to ask how much a broom costs. Or he might tell you that Santa doesn’t employ fairies because fairies don’t exist. Tuck had four different favourite colours. He believed in ghosts and liked to talk to them in the litter tray. You get the picture? He was one crazy cat.

But Tuck was also a real athlete. You might call him a lean, mean, fighting machine, except he mostly lacked the courage to fight anyone but Ginger. Unlike Ginger, Tuck had no fat on him at all. When he was chasing string, you could see the muscles ripple under his coat, and his belly was as firm as a brand-new tennis ball. Tuck was black, as black as a panther. His fur, nose, whiskers, the pads on the bottom of his feet and even his claws were all pitch-black. Naturally, this was something of which Tuck was very proud. The only things about Tuck that weren’t black were his razor-sharp teeth (sparkly white), his sandpaper tongue (pink), and his amazing hunter’s eyes (green or yellow, depending on his mood). In the dark, Tuck’s body disappeared completely, and all you could see were those huge flashing eyes and (if he was smiling), all those white teeth. He was like a Masai warrior, proud and stealthy in the night but scared of vacuum cleaners.

Inevitably, there were fights. Oh boy, did Tuck and Ginger fight! Have you ever heard of the expression ‘the fur will fly’? You haven’t? You should get out more and talk to people; it’s a very common expression.

Anyhoo, when these cats fought, the fur would definitely fly—huge clumps of black or ginger cat hair wafting through the apartment where the two of them lived. If Tuck found Ginger on his favourite spot on the back of the sofa, he’d pounce on her and bite her ears until he could taste wax. Or if Ginger found Tuck on the double bed upstairs, well, hoochie baroochie, all hell would break loose. Tuck would kick Ginger in one of her six bellies, and Ginger would bite Tuck on the back of his neck. She’d hold him in a tight half nelson with her front paws and jab him in the face with her back paws. He’d pounce on her, she’d spit at him—bish bosh, crish crash—day after day after day. No claws of course as they were both decent adult cats after all, but you could never have described the two as friends. Well, you could have, but you’d have been wrong. Ginger, you see, thought Tuck was stupid, and Tuck thought Ginger was arrogant.

Now, generally when Tuck was being Tuckish, Ginger would just roll her eyes and sigh. But last year, on the day this strange and terrifying story starts, Tuck said something that changed everything and started our furry felines on an adventure where they would have to stop fighting each other and start fighting for their lives instead.

It was towards the end of autumn, and Ginger was sitting on the windowsill of the apartment where she and Tuck lived. This apartment was on the fourteenth floor of a tower block in the middle of a huge city. The apartment had an upstairs and a downstairs, like a house, but what it did not have was a garden or even a balcony, which meant Tuck and Ginger never went outside. As a result, Ginger liked to spend the little free time she had (after eating, sitting in the litter tray, fighting Tuck, and sleeping fourteen hours a day) looking out the window.

From her windowsill Ginger would watch carefully to see what she could see. Some days she would see nothing all day—just the same sky, the same trees, the same apartment blocks down the street. On other days she’d be lucky and see people and dogs and children passing by. Best of all were the days when she saw another cat. Ginger had very good eyes in those days, and she could spot a cat from anywhere. Whenever she did, she’d wonder where it was going, what adventure it might be about to have, or what types of dead food it might find on the street. If she saw a cocky cat down on the street, she’d bristle her fur and imagine scratching him on his nose and chasing him away.

Or sometimes Ginger would see a bird. Whenever she did, she’d shudder her bottom jaw and dream of catching the little thing and eating it. But mostly she’d just sit and look out at nothing and wonder if she’d ever go outside again. For this is what Ginger wanted more than anything in the world—to breathe the air of freedom and get back to the life she’d once had.

For four years now Ginger had lived in this apartment, and not a single day had passed that she hadn’t dreamt of escape. She’d calculated the distance she’d have to jump to land in the nearest treetop should a window ever be left open. She’d tried climbing into her owners’ luggage whenever they packed to go away. She’d even once tried signalling to a cat she sometimes saw in another apartment block across the road. But all to no avail.

And now, as Ginger sat looking out of the window, she realised she was getting old and fat and would probably never go outside again. Six bellies took a lot of filling, and she wondered if her hunting skills were what they once had been. And of course, she wasn’t as vibrant a redhead as she used to be.

Ginger tried not to let herself think this way. She tried to think of positive things, but sometimes on a sunny afternoon

the only noise in the apartment (when Tuck wasn’t singing) was the sound of big, gingery sighs.

Ginger’s view of the outside world was better in the autumn. All but the stubbornest of leaves had fallen, and she could see through the bare branches of the trees outside the window. There, in the distance, she could just make out the edge of the city and the beginning of the countryside. If she squinted, she could make out fields and hedges; she could remember the feeling of grass beneath her paws, remember how good it tasted, remember lots of things. That morning she had just let out a long and particularly gingery sigh when Tuck came trotting along.

‘I want to go to the moon,’ he said. ‘I have a feeling the entire thing might be made of mushroom sauce.’

Ginger looked down at him. His huge eyes were bright yellow as they reflected the pale sunlight coming through the window. Now, if you’d asked Tuck what colour his eyes were at that moment, he’d have guessed green, because they were generally green when he was happy. But there were no green leaves left to reflect green light, so he sat there, happy with yellow eyes. ‘Why was Tuck happy?’ I hear you ask.

I said, ‘“Why was Tuck happy?” I hear you ask.’

Hello?

Aha, yes, I thought you’d ask that. Well, Tuck was happy because he’d had a Big New Idea. And this made him happy for two reasons. Firstly, it annoyed Ginger. Secondly, it gave him something to think about. So, what was the Big New Idea, I hear you ask? I said … Oh, don’t bother, I’ll do it myself. What was the B.N.I.? Well, the previous night Tuck and Ginger’s owners had poured mushroom sauce on their dinner. Oh, wemjee!

I have to tell you about Tuck and Ginger’s owners!

You’re going to love them! Well, hate them!

Love hating them!

They … Oh, look, it’s going to have to wait, otherwise this story is never going to start. Remind me in a minute, will you?

So the night before this story starts (if it ever blooming well starts), after the owners had eaten their dinner, Tuck snuck into the kitchen. He wasn’t allowed up on the kitchen surfaces, but he reckoned once the TV was on, it would be ages before his owners-who-I-have-to-tell-you-about would come back in to tidy up. So he jumped up and started licking their dirty plates. And what did he find there? Mmmmmushroom sauce. Yummy, yummy, yummy. Well, Tuck lapped it up, and pretty soon he had decided mushroom sauce was the best food in the whole wide world. He told this to Ginger later that same night. Do you know what he said? He said, ‘I think mushroom sauce is the best food in the whole wide world.’

Of course, Ginger just ignored him. She sighed and curled up tighter in the corner of the sofa where she liked to sleep at night. Then she sighed again. She couldn’t be bothered telling Tuck about grass or cream or sardines or any of the far better foods she’d tasted on her travels. She merely licked one of her paws, gave him one of her looks, and put her nose under her arm. Secretly she agreed that mushroom sauce was pretty spectacular, but she’d be a tabby before she’d admit that Tuck had spoken some truth. And she knew he’d soon enough forget about it again.

But the next day proved her wrong. Here was Tuck, a full twelve hours later, still going on about mushroom blooming sauce. It was going to be a long day.

‘If the moon is made of mushroom sauce and we went to the moon, we could have mushroom sauce whenever we wanted,’ he said, looking up from the floor and ignoring Ginger’s obvious disinterest. ‘I really want to go to the moon.’ He started singing.

‘Fly me to the moon,’ he sang. ‘Let me walk amongst the stairs. Show me what springs look like on Jupiter’s sandbars.’

Now, there was little in the world that Ginger hated more than Tuck’s singing. He was often off-key and always got the words wrong. Worst of all, Tuck sang almost all the time. Ginger stuck her two front paws way out in front of her and curved her back in as much as she could. Then she stuck her bum way up in the air and wiggled her tail slightly. She was going to jump on top of Tuck from here on the windowsill and see how he felt like singing then. She was just checking her position, quivering her tail and steadying her paws, when Tuck stopped singing and said, ‘Oh, by the way, the cleaning lady left the front door open.’

‘What?’ said Ginger.

‘She left the front door open. I saw into the corridor. It’s got a carpet which is very close to two of my favourite blues.’

Now Ginger did jump. But not onto Tuck, for that would be a waste of valuable time. Instead she jumped to the floor and ran full speed towards the front door of the apartment. It was indeed ajar.

‘Oh, sweet Tabatha,’ she said.

‘It’s a kind of a pastel blue,’ said Tuck, who had followed her. ‘Or maybe cornflower. But cornflower’s flowerier … Oh, look—a fly!’

With that he ran off, chasing the fly into the kitchen and leaving Ginger transfixed by the open door. Tentatively, without shifting from her spot, Ginger put her head forward and sniffed the air in the blue-carpeted corridor outside the apartment door.

Now, wasn’t there something you were supposed to remind me about? What was it?

Oh yes! Tuck and Ginger’s owners! You’re going to love them, hate them … oh, have we done that bit? OK, here we go.

As far as the outside world was concerned, Rodney and Janice Burringo led very normal lives. They lived in an apartment with their two cats, shopped once a week at the supermarket, and went to office jobs which no one really understood.

Have you ever noticed that, by the way? No one really completely gets what anyone else does all day. It’s weird, even if people used to do something themselves, they don’t get what it’s like when anyone else does. Like when you come home from school and your mum or dad or resident adult says, ‘How was school today?’ Next time they do that, I suggest you say, ‘Did you ever go to school?’ and when they say, ‘Yes’, you can say, ‘Well, it was like that’. Then you can get on with picking your scabs and drawing pictures rather than answering their stupid questions.

Bennyhoo, Rodney and Janice Burringo were not normal people and did not lead normal lives. They only pretended to go to work. As soon as no one was looking, they’d sneak back to their apartment and sleep all day in the secret-upstairs-locked room that even the cats weren’t allowed in. (Ginger had been caught in there once and was so severely punished that Tuck trembled just passing by the door.) The secret-upstairs-locked room was a very dark room with no windows. It contained nothing but a clothes rail where Rodney and Janice would hang their work clothes so they could sleep naked on the floor. They had to do this because in reality Rodney and Janice were …

Wait for it …

Can you guess?

No, not vampires! What is it with everyone and vampires these days? Get over the vampires thing already, it’s so last season. No, Rodney and Janice Burringo were witches! Evil, nasty witches. What do you mean, men can’t be witches? Get out of here with your outdated prejudices. Men and women can be whatever they want. And what did Rodney and Janice want? Durrh. They wanted to be witches!

You know how most people have saucepans in their kitchen cupboards? Rodney and Janice had cauldrons. You know how most people clean their house with a vacuum cleaner? Rodney and Janice did it with broomsticks (although they did keep a vacuum cleaner just because they knew Tuck was terrrrrrified of it—see how nasty they were?). And at night they would sneak up to the roof of their building with these broomsticks and launch themselves into the air, cackling loudly and scaring anyone who might be passing by. Then they’d fly all over town, leaving things where they shouldn’t be. Rodney had a big bag of dog poo, and he’d leave little piles of it on the pavement outside doorways. Janice had a sack of litter, which she’d distribute in windblown alleyways. Witches love litter. It gives them little tingles up their warty spines, and you must be very careful not to walk along a littery road after dark in case a witch finds you there. You really don’t want to be found by a witch, did you know that? And do you know why? Because witches just love children. Mostly they liked t

hem fried, but Rodney and Janice preferred them grilled because it’s a healthier way of cooking with less cholesterol. Best of all, though, for witches all over the world, is lightly steamed child in a white wine sauce.

Yummy yummy YUMMY!

It was as a result of the Burringos’ activities that Ginger and Tuck had so much time to themselves. At night Rodney and Janice would be flying all over the city doing their dastardly deeds, and during the day they’d both be fast asleep in the secret-upstairs-locked room. Now, you might be wondering why the Burringos bothered having cats at all, and that is indeed a good question. It wasn’t because they’d got pets before thinking how little time they’d get to spend with them like some idiotic people do. Oh baloney no. It was because … well, it’s an important and interesting story, which I will tell you. But in the meantime, let’s get back to Ginger.

THE FIRST AND A HALF BIT

Where were we? Oh yes. Tuck is chowing down on a fly in the kitchen, and Ginger is still standing at the apartment door. The open apartment door. How did I put it last time? ‘Ginger sat transfixed by the open door’—something like that. Well, tentatively, without shifting from her spot, Ginger put her head forward and sniffed the air in the blue-carpeted corridor outside the apartment. It didn’t smell like freedom. It smelled like dried baby-sick and cleaning fluids. To you or me it would just have smelled a bit fusty, but cats have got the most amazing noses, and they can be much more precise than us. As far as Ginger could tell, there was some 2006 carpet cleaner with hints of burnt-out light bulb. And baby-sick of course. The baby-sick must have been ancient, as Tuck and Ginger hadn’t heard Baby crying next door for years now. I wonder what happened to him?

Bendyway, Ginger sniffed the air again until she thought, ‘What am I doing? I’m still standing here like a scaredy-cat when I should be out there like a brave-cat.’ Still, she didn’t move. She realised she was terrified, and it was this very realisation that drove her forward. For Ginger knew that the difference between brave-cats and scaredy-cats isn’t fear. It’s how you act. Brave-cats feel the fear and do it anyway. Scaredy-cats feel the fear and run like bonkers. And which do you think Ginger was?

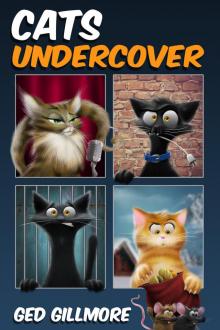

Cats Undercover

Cats Undercover Cats on the Run

Cats on the Run Cats On The Run (Tuck & Ginger Book 1)

Cats On The Run (Tuck & Ginger Book 1)