- Home

- Ged Gillmore

Cats On The Run (Tuck & Ginger Book 1) Page 6

Cats On The Run (Tuck & Ginger Book 1) Read online

Page 6

Ginger didn’t respond. She was trudging along beside him, half asleep. She’d been walking like that for hours. Occasionally she’d fall fully asleep and walk in a weird diagonal that cut across Tuck’s path. Then she’d nod suddenly and wake herself up.

‘Got to keep going,’ she’d say. ‘Got to. Keep. Walking.’

But eventually even she had to stop. Actually, I don’t know why I say ‘even she’. It’s not like Ginger is a robust specimen of feline health and resilience, is she? She’s a fat ginger cat with six bellies. Now, Tuck, Tuck’s a different story. Tuck, could probably have gone on for a while. The point is: Ginger had to stop. The two cats hadn’t eaten that night—they had seen no rats for Tuck to play tick with—and they hadn’t stopped walking either. So, by the time the sky began to soften and a dull glow appeared in the east, by the time they suddenly found themselves in the countryside, both of them were tired and hungry.

‘I have to stop,’ said Ginger. ‘I need somewhere to sit and rest.’

‘What about that big building?’ said Tuck.

Ginger’s eyes were heavy and half closed, but she still managed to roll them in disdain.

‘That’s not a building, you moron.’ She yawned. ‘That’s a hedge.’

‘No,’ said Tuck. ‘Look through the hedge. It’s a building!’

Ginger squinted through the thick leaves of the hedge beside the road. Tuck was right. A huge old hay barn lay in the field beyond. What a feast for sore eyes!

‘Perfect,’ she said. ‘We’ll rest there. And it’ll be full of mice, which you can help me catch.’

‘You said they were rats,’ said Tuck.

‘I said they were rats and they were. But this is the countryside. We’re more likely to see mice now.’

‘Why?’

Ginger took a deep breath. She wasn’t too tired to pin Tuck to the ground and kick him in the ears.

‘Because,’ she said, ‘on the moon all the rats are terrified of mushroom sauce, so they stay in the cities. Come on, are we going to this barn or not?’

‘What’s a barn?’ said Tuck.

‘It’s a kind of spaceship left behind by aliens,’ said Ginger over her shoulder as she crawled under the hedge.

Coming out the other side, she found herself in a broad green pasture covered in cowpats. She could see the cows far away on the other side of the pasture, and the sight of them made her feel better. She felt like she was getting closer to home. Then as Tuck crawled under the hedge behind her, asking if the cowpats were made of sauce too and what a barn was again and were they nearly there, Ginger walked across the grass. Well, that made her feel even better. Cats love grass—it relaxes them and puts big fat smiles on their faces.

‘Ooh hoo hoo,’ said Tuck. ‘This green stuff tickles. Ooh, it tastes good too.’

Of course! Ginger had been away so long she had forgotten she could eat grass. She stopped and started nibbling on it, then turned her head to crunch it with her side teeth. ‘We’ll be seeing this again,’ she thought as she ate it, but she carried on regardless. At least it was food. She felt better than she had done in hours. But she knew they should rest, sleep, and eat something they could keep down, so she told Tuck to keep up and walked on to the barn.

Close up it looked even bigger than your average barn. It was a ginormous great building with one side open to the elements.

‘What’s that stuff?’ said Tuck, pointing inside.

‘It’s hay,’ said Ginger. ‘It’s where the mice live.’

There was plenty of it, huge piles reaching up to the ceiling, tied in bales like giant Lego blocks.

‘What’s Lego?’ said Tuck.

‘What?’

‘I mean, what’s hay?’ said Tuck.

‘It’s dried grass. It’s scratchy, warm, and good to lie in.’

‘Ooh,’ said Tuck. He looked at the great stacks, all of different heights, some only one or two bales tall, some reaching all the way up to the ceiling. Then he took a deep breath and said ‘Ooh’ again.

The two cats walked in through the great open side of the barn, looking up around them. Have you ever been in a truly huge building? Not one with lots of floors, I mean one with nothing but air between you and the top? Like the Blue Mosque in Istanbul or St Paul’s Cathedral in London or Grand Central Station in New York? Other buildings may be bigger, but empty buildings feel bigger because you can see further. It’s done on purpose in religious buildings to make you feel smaller and more in awe of a bigger power. I’m not sure why it’s done with train stations—maybe you can get back to me on that one. In barns it’s done so that it’s easier to stack hay, but the end effect is all the same: awe.

‘Wow,’ said Ginger. ‘Awesome.’

‘I wonder if anyone lives here,’ said Tuck.

And then the whole barn echoed to a booming voice, which belonged to neither of them.

‘Of course somebody lives here!’ it shouted, filling every corner of the cavernous barn. ‘I do!’

Now, the more observant of you may have noticed that every time something exciting is about to happen in this story, I whisk you away and start telling you about what was happening on the other side of town. It’s a cheap narrative trick, but if you’ve got this far, it seems to be working. Except now of course I can’t do it. Two reasons. Firstly, the cats aren’t in town anymore, they’re in the countryside. Or ‘the bush’ as they call it in Australia. I’ve no idea why Australians call it ‘the bush’. It’s not like other countries don’t have bushes in their countryside. Maybe it’s because it’s a shorter word? Australians like to abbreviate everything, and ‘bush’ is as good an abbreviation of ‘countryside’ as anything else I can think of.

The second reason I can’t whisk you away to the other action is because Janice and Rodney are in the secret-upstairs-locked room, snoring away on the floor. Not sure why they’re still locking it now the cats are gone, but people are strange and witches are stranger. But whisk you away I will. Not to the contemporary action but to glance at Ginger’s history.

You see, I’m thinking you are probably wondering why Ginger was so keen to get back to the countryside-slash-bush. Life at the Burringos’ was rather good, after all. A steady supply of food, plenty of soft surfaces to laze the day away on. What could it possibly be that drove Ginger to brave the elevator, risk the wrath of the Burringos, and face starvation and exhaustion on the road? The answer—as is so often the case—is love.

Oh yes. Ginger might have been the original badass-from-the-back-of-maths-class, she might have been as tough as old nails, as sarcastic as a caustic car sticker, as bolshie as a belching butcher from Bendigo, but underneath that Ginger exterior she had a woman’s heart. Well, a female cat’s heart, but you know what I mean. And even though it was quite far underneath the exterior because of all the bellies and other residual fat, it was a big heart nonetheless. A heart that beat in time to another cat’s heart.

I’m not sure anyone really knows how Ginger first met Major ‘Mango’ Awesome.

It might have been when she was working the clubs in Berlin. (She was a lighting technician; he played triangle in a few of the bands.) Or when she was learning to cook in the South China Sea. Or, I suspect, their paths crossed on the alley-fighting circuit. Either way, from the moment they set eyes on each other, it was fond and feline feeling all the way.

Ginger was a city cat through and through, Major was a country boy, and yet they found they had so much in common. They’d lie on a car roof at night, passing each other stalks of grass and talking about their lives, amazed at how often they’d been in the same place at the same time, passing within a whisker of each other and yet never meeting. Ginger would tell Major of the things she loved and find he was the only cat she’d ever met who knew what she was talking about. Major would express his frustration at the way of the world, and Ginger would say exactly what he needed to hear. He’d finish her sentences, she’d guess what he was thinking about, he’d teach her a new purr he

’d heard on the road only to find she knew it too. Ah, love.

Only four weeks after first meeting Major, Ginger thought nothing of hanging up her knuckle-dusters, leaving the city behind, and moving out to the abandoned stables where Major lived, deep in the countryside. And he thought nothing of letting her boss him around, telling him to tidy up and rid himself of his bachelor habits. It was a good life.

But as ever with the good things in our lives, we grow used to them too quickly. Luxuries become necessities, contentment becomes wondering ‘what if’, comfort becomes boring. Soon both Ginger and Major remembered that they had once been ambitious for more. They both missed their lives on the road. ‘Let’s save up,’ said Ginger. ‘Let’s buy a one-way ticket to somewhere and see what happens next.’ And so they’d started driving the taxi, taking turns so when one of them was sleeping, the other was driving. It meant commuting to the city and seeing each other less often, but they both figured it would be worth it in the end.

Well, this little living arrangement was all going fine and dandy until one night Major and Ginger had a terrible fight. It was about nothing—all the big fights are—and it was about everything. Have you ever heard adults argue? Awful, ain’t it? But it’s part of life, part of living together, and cats are no different.

On the night in question, Ginger and Major had a real humdinger. They ended up on the stable floor, doing that low whiney moan which cats do when they are seriously unimpressed. Nnnngggggeeeeeeuuuuugggghhhh. Then Ginger said, ‘Eat my litter’, and walked out in a big huff. She threw her possessions into the boot of the cab and drove off. Of course as soon as she reached the city she realised what a mistake she’d made. She tried calling Major from a call box but then remembered there was no phone at the stables. So she turned the cab around and started driving back to say sorry, to say they should work it out. To tell Major how much she loved him and how much she wanted to be with him forever. Just then she saw a nice-looking man on the sidewalk, looking for a cab. ‘Oh well,’ thought Ginger. ‘I’ll just do this fare and then I’ll drive home.’

Except of course that nice-looking man was not nice at all. He was not a man at all—he was evil Rodney Burringo, the kidnapping old buzzard. And the rest, as they say, is this story. Or the bit before this story and then this story if you want to split hairs about it (which I know you don’t). Poor Ginger! She had no way of letting Major know she hadn’t left him. No way of telling him she’d never do that. All she wanted to do was get back to him as fast as she could.

Meanwhile back in the barn … Oh no, not meanwhile at all. Actually, it’s four and a bit years later back in the barn. Ha, and you thought you were sharp. So, back in the barn …

‘I wonder if anyone lives here,’ said Tuck.

And then the whole barn echoed to a booming voice, which belonged to neither of them.

‘Of course somebody lives here!’ it shouted etc. ‘I do!’

Ginger spun around in an instant, tail puffed up and claws at the ready. Tuck couldn’t even do that. He was entirely frozen to the spot in panic. It was just like the most frightening scene from his least favourite horror movie when Dorothy and her friends go to see the wizard for the first time.

‘Who,’ said the booming voice, ‘are you?’

Tuck was shaking so hard he could hardly stand. If he wasn’t such a well brought-up cat, he’d have wet himself there and then. Ginger came over and stood next to him, pressing against him to stop him shaking.

‘We,’ she said, ‘are two cats who are not afraid to show our faces. What about you?’

‘No,’ Tuck whispered to her. ‘Don’t upset the mighty wizard! He might do that thing with the green smoke.’

But Ginger coughed a little and let out a huge yowl. ‘Out! Come on out, you coward.’

‘I am out,’ said the booming voice. ‘Up here.’

Now Tuck turned, leaning on Ginger as if she was the back of a sofa. The two of them looked up to a rickety wooden ledge high above the open entrance to the barn. There sat a row of six cats looking down at them. There was a lean black cat with white patches and a muscular tortoiseshell cat with weird eyes. There were two hugely fat tabbies, who were obviously father and son, and a beautiful Siamese. And the last cat—much to the horror of Tuck (and Ginger, except she didn’t admit it)—the last was pure white. Yikes! There is little more dangerous in life than a pure white cat. They scratch, man, they scratch bad. Next to the white cat, who was actually the smallest of the six, was a metal stand that held the biggest megaphone you’ve ever seen in your life. Well, if you’d seen it, it would be the biggest, but this will have to be the biggest megaphone anyone’s ever described to you. Huge, really. As Ginger and Tuck watched, the mean, evil, scratchy-looking white cat leaned towards it.

‘Now,’ she boomed. ‘Who are you?’

Tuck gasped in horror as Ginger burst out laughing.

‘A megaphone!’ she said, chortling away and making Tuck bump alongside her as she shook with the laughter. ‘A megaphone! If you had any self-respect, you’d come down here and speak to us cat-to-cat. Or at least shout down. Ha! A megaphone she needs!’

‘Ssh!’ said Tuck. ‘Don’t upset her. She’s white.’

But it was too late. The little white cat looked very upset, and the other five cats looked upset about her being upset. Well, four of them did. The Siamese just sat there and looked beautiful—you know what they’re like.

‘Oh,’ said Tuck. ‘Oh, maybe we should go? Maybe we should just move slowly to the exit, and they’ll forget we were ever here.’

‘Tuck,’ said Ginger, ‘if you move so much as a muscle before I tell you to, I’ll bite you so hard that I’ll have to go to the litter tray to get rid of the fur ball. Do you understand?’

She said it with a fixed smile on her face and in a voice Tuck had never heard her use before. He sat down and nodded slowly. High above them the little white cat had walked to the edge of the ledge. She was yelling something down to them, but all they could hear was a faint squeak, which might have been from one of the swallows that was flying between the rafters.

‘Sorry,’ said Ginger. ‘I can’t hear you.’

The white cat tried again. She seemed to be trying with all her might, her eyes squeezed shut and her tail waving in the air behind her. From the corner of her eye Ginger could see Tuck had stood again and was moving around strangely, but she ignored him and stared up to the ledge.

‘Can’t hear you,’ said Ginger. ‘What?’

So the little white cat went back to the megaphone and leant in towards it.

‘I had throat cancer last year,’ she boomed. ‘I had an operation, and now I can make myself heard only through a megaphone.’

‘Ooh,’ said Tuck, nudging Ginger in the side. ‘That’s embarrassing.’

‘Rubbish,’ said Ginger quietly. ‘It’s not embarrassing at all. She’s probably making it up.’

‘Why are you blushing then?’

‘I never blush!’ hissed Ginger under her breath.

‘Well, that’s weird because you’re blushing now!’

Hang on a second, I can hear you thinking. Hang on, hang on, hang on. Wasn’t Tuck only two minutes ago quaking in his paw pads? Where has all this cheekiness come from? Oh, go on then, I’ll tell you anyway. It was the slinky Siamese up on the ledge. While the white cat had been trying to make herself heard using just her voice, the Siamese had smiled at Tuck. Then she’d winked at him. Then she’d slowly licked one paw and, all the while holding eye contact with him, wiped it across her ear. Hoochie handbags! Well, Tuck forgot all his fear at once and started waving back like a madman until Ginger’s embarrassment distracted him.

‘Ha ha,’ said Tuck. ‘You’re embarrassed.’

Ginger ignored him. ‘Why are you all up there?’ she shouted up to the ledge.

It was the flabby tabby daddy who answered. ‘We can’t come down there’ he said. ‘There’s rats.’

Tuck looked at Ginger smugly, but she ignored

him.

‘Huge rats,’ said the tortoiseshell, scouring the floor with his weird eye. ‘They bite.’

‘Rats?’ said Ginger. ‘Rats are food! How can they be frightening?’

The white cat leant into the megaphone again. ‘We don’t eat meat in this commune,’ she boomed. ‘We don’t believe in hurting other living beings.’

‘Right,’ said Ginger. ‘So what do you eat?’

‘They give us dried food up at the house,’ said the flabby tabby babby. ‘It’s yummy and stops our poo from smelling.’

After that, none of the other cats could think of what to say.

A BIT WITH A BAZOOKA

Half an hour later Tuck and Ginger were high up on the ledge with the barn cats. The black-and-white cat had introduced himself as Harry and invited them up. ‘All are welcome here,’ he said. ‘You have nothing to fear.’ So up and up the bales of hay Ginger and Tuck had climbed. Ginger was fearless of course but slow, stopping on every bale to drag her bellies up after her. Tuck could get from one bale to another in one easy spring, but after only four or five bales, he started whimpering at how high up he was.

‘Don’t look down,’ said Ginger. ‘Concentrate on helping me instead.’

‘But …

‘No buts,’ said Ginger. ‘Here, see if you can drag this last belly up for me.’

Well, helping with six bellies is difficult when you can’t count past three, and before Tuck knew it they were at the top. The first thing Ginger did was quietly and quickly apologise to the little white cat for her insensitive comments. The little cat shrugged and said something in reply, which Ginger couldn’t quite make out. Rather than ask the white cat to repeat herself, Ginger walked over to the others and introduced herself.

‘I’m Ginger,’ she said, ‘and this is—’

‘Tuck! Hi! I’m Tuck, hi, everyone,’ said Tuck, jumping around excitedly. ‘My name’s Tuck. Hello, hello.’

The flabby tabbies introduced themselves as Barry and his son, Larry. They were from Gary, Indiana.

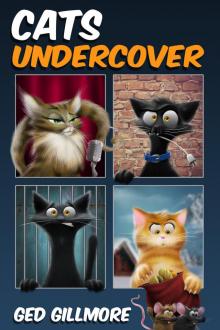

Cats Undercover

Cats Undercover Cats on the Run

Cats on the Run Cats On The Run (Tuck & Ginger Book 1)

Cats On The Run (Tuck & Ginger Book 1)