- Home

- Ged Gillmore

Cats on the Run Page 11

Cats on the Run Read online

Page 11

When a fox running at full hunting speed trips in a forest in the middle of the night, does it make a sound? Yes, it blooming well does. It goes bang, crash, wallop, cacrumble, snap, crump, crump, caproomph - crash, tinkle-tinkle boomph!!! Bang. Clatter-clatter bump.

Ginger peered over the log, hoping desperately it was only Snarlsgood that had made this racket and that he hadn’t caught up Tuck in his cacophonous carnage. But it didn’t look good. All she could see was a broad trail of leafless ground with broken twigs thrown up either side. At the end of this trail was a crumple of fur with little stars circling above it. There was no sign of Tuck. Ginger climbed up slowly onto the log and peered back towards the dark and silent trees. Hopefully, the fur she could see was brown and foxy and not black and Tucky. She peered closer still.

‘Tuck?’ she called. ‘Tuck, are you OK?’

‘Hiyaaaa!’ said Tuck, jumping up from the other side of the log. ‘Surprise!’

‘Cheeses!’ said Ginger as every single hair on her body stood on end. ‘Don’t do that. I thought … Well, I thought I was very clever just then.’

‘Me too,’ said Tuck. ‘I jumped down behind the log, and he must have tripped, and I’ve killed him.’

Ginger did one of those big ginger sighs I keep talking about and rolled her eyes. ‘He might not be dead,’ she said. ‘Go and check.’

‘No,’ said Tuck.

‘Go on.’

‘No.’

‘Who tripped the fox?’

‘Ginger did.’

‘That’s right,’ said Ginger, and she hopped down onto Tuck’s side of the log and started walking gingerly up the trail which the tumbling Snarlsgood had left in his wake. She managed about four steps, which is only one step really if you count all four paws.

‘No,’ she said. ‘Not dead. Just unconscious. You can tell by the stars. If he was dead, there’d be a little foxy angel with a harp floating upwards. We’d better get out of here.’

Tuck did not disagree, and so the two cats hopped back over the log and walked on deeper into the forest. Not the way their noses told them they should go, because the fox might come after them that way, him having instincts too. Instead they went off to the right a bit and then winding in and out of huge trees and under thick bracken and finally crawling under thick and thorny brambles. By the time they were too tired to walk any further they were completely and utterly lost.

BLOOMING HECK, IT’S ANOTHER BIT

MIAOWNWHILE, back at Burringo Towers, the witches had woken up.

‘Pooh,’ said Janice. ‘There’s a poo!’

‘Oui,’ said Rodney. ‘There’s a wee!’

‘Scratch that!’ they both yelled together. ‘Look at our stair carpet!’

‘That cat is pure evil,’ said Rodney, searching for a paper towel under the sink with one hand and pointing at Major with the other. ‘Evil and bad.’

‘Evil and horrible and awful,’ said Janice.

‘In fact,’ said Rodney, ‘he’s perfect!’

‘Too darling for words,’ said Janice, and before Major could react she’d swooped him up in her skinny arms. ‘Oh, my preciously poisonous pussy,’ she said. ‘You’re going to make the purrrfect Purrari.’

Major gave her his best attempt at a smile, but he couldn’t bring himself to say anything and so bit her instead.

‘Ooh!’ said Janice, dropping him to the floor in that way that all cats hate. ‘Ooh, he bit me! Terrible, terrible, awful, dreadful, marvellous, perfect cat!’

‘Janice,’ said Rodney, ‘do calm down or you’ll—’

But it was too late. The apartment was filling with Janice’s green bum gas. ‘I can’t help it.’ She laughed. ‘I’m so excited. Darling Rodders, let’s go and find ourselves a black cat straight away. We have everything we need for the mingle. Please? Pwease, Rodder Dodder, pwease can we?’

‘You must be off your buffalo,’ said Rodney, picking up the cat poo from the kitchen surface and throwing it into a bag for distribution at a later date. ‘I’m cream-crackered. The last thing I want to do is go down to the dog home and get another blooming cat. You go if you’re so keen, but leave me out of it.’

Ouch. Did I mention that Rodney wasn’t an early-evening kind of person? Some people really are at their worst when they first wake up, and some witches are no different. Well, Janice was far too excited to let some miserable grotbag of a husband burst her bubble.

‘Fine,’ she said. ‘I will! Just you watch.’

‘I’m watching,’ said Rodney.

And he was. He sat himself down on the sofa without washing his hands, crossed his arms, and watched Janice find her purse (English), put it in her purse (American), purse her lips, give him a rude gesture, and walk out the front door. Major watched all of this with great interest, and as Janice left he went running after her as fast as he could. But before he could make it out of the apartment, Janice had slammed the door behind her. Boy, did that make him grumpy.

It was a little over an hour later when Major heard Janice returning. Have you ever noticed how cats can do that? They can hear people coming before humans can. It’s a quality they share with dogs (much to their disgust) and is not—as you may have assumed—based on their animal sixth sense. It’s based in fact on the fact that factually their faculty of hearing is better than ours. They hear at much higher frequencies and can distinguish between the jingle jangle of keys at a distance greater than we could ever imagine. So there. But Major didn’t hear only a jangle of keys approaching from outside the apartment door. There was another noise too, a squeaking, wiry noise that sounded suspiciously like a cage with a cat in it.

‘I’m hungry,’ said Tuck.

He and Ginger had awoken in a strange part of the forest. For the most part there were very few plants on the ground, just huge bare trunks of trees that stretched way up into the sky with, here and there, thick patches of rough grass, great tufts of grey-green blades which drooped or swooped as a breeze came through. It was noticeably cooler here than in the thicker parts of the G.D.F. and certainly the coldest temperature they’d experienced since leaving the apartment. It was as if summer had become exhausted overnight, given up the fight, and handed things over to autumn. On the few occasions when they could see through the canopy high above them, all they could see were dark, grey clouds.

‘I’m hungry,’ said Tuck again.

‘And tired?’ said Ginger.

‘Yes!’ said Tuck. ‘How did you know?’

‘Because you’ve told me about a hundred times since we first woke up. Shut up for goodness sake and keep walking.’

Now this sounded a little harsh even to Ginger, who was a harsh cat. So after a few minutes she said, ‘Try not think about it’. She might well have said it to her own bellies too. ‘I’m even hungrier than him’, they said one after the other, although of course they said it in Tummeze, which sounds to you and me just like gurgling and rumbling. Tuck’s stomach called back to them, as hungry tummies often do, and as the cats walked slowly through the forest, it sounded to the ants and lice like a storm approaching. On and on Ginger and Tuck walked, their sense of direction totally thrown but somehow still guiding them in vaguely the right direction. Or at least they hoped so.

It was a long, dry day. They left the half-grassy forest behind and entered a part of the wood with nothing but bare dirt on the ground. Then they left that for a part where the huge trees were replaced by medium-size trees. Then, towards the end of the day, they found they were walking downhill. To their joy they found a little creek. They hadn’t realised how thirsty they were, and they lapped at the clear, cold water in long and lazy licks. Tuck would have purred, but he was too tired and hungry to do even that.

‘It’s nice, isn’t it?’

‘Yes,’ said Tuck.

‘What?’ said Ginger.

‘You said it was nice,’ said Tuck.

‘No, you said it was nice.’

‘I didn’t say that.’

‘Well,

if you didn’t say it and I didn’t say it …’

Both cats stopped drinking and looked up slowly to see who had said the water was nice. They hoped to goodness it wasn’t a fox. They looked over the stream and saw nothing. They both looked to the left and saw nothing. Then they both looked to the right and saw nothing. Then they both looked behind them and saw … nothing! Just trees as far as they could see, medium-size trees nearby, bigger trees beyond them, a group of four knobbly saplings right behind them.

‘Ooh dear, don’t stop drinking on my account,’ said the voice again.

Well, where else was there to look? No! Not down! Not unless you think worms and woodlice are wont to willingly woo you by wantonly wanging on and wasting words about water. No, no, no. Both cats looked up, and there, right above them, they saw a huge, furry animal with massive great antlers. Those four saplings behind the cats hadn’t been saplings at all but legs—furry legs with hooves on one end and a massive great stag on the other.

‘Agh!’ yelled Tuck. ‘It’s a huge furry television transmitter monster!’ and he jumped backwards over the creek in a not unimpressive double salto. Ginger rolled her eyes and—you guessed it—sighed.

‘Ooh dear,’ said the deer. ‘What’s wrong with him, dearie?’

‘He’s never seen a deer,’ said Ginger to the deer. ‘Not in your way, are we?’

‘Ooh no, dearie,’ said the deer. ‘There’s plenty for everyone, I’m sure. You two are a long way from home aren’t you? You lost, need any help?’

Well, as you can see, the deer seemed pleasant enough, so Ginger told him their story while Tuck looked on warily from the other side of the stream. He couldn’t stop staring at the deer’s huge antlers, which were, it has to be said, quite extravagant.

‘What are they for?’ Tuck said at last, when Ginger had reached a pause in her story and was having another sip of water.

‘What, dearie?’ said the deer.

Tuck pointed up at the antlers, and the deer snorted.

‘Well, dear,’ he said. ‘Don’t tell anyone, but I use mine for getting national radio and drying my undies. Some boys use them to fight with, but I can’t be doing any of that. They’re furry—would you like to feel one, dear?’

It didn’t seem quite proper to do so, but it didn’t seem polite to refuse, so when the deer stepped into the stream and dipped his head towards Tuck, Tuck reached up a paw and stroked the antlers.

‘Ooh,’ he said, ‘furry.’

‘He he he,’ said the deer. ‘Careful dear, it tickles.’ Then he said, ‘Ooh, I have an idea’, and before Tuck knew quite what was happening, the deer had taken another step forward and swooped him up in his antlers. ‘Look, dear,’ said the deer. ‘You can probably see much further now and find your way home.’

Ginger put her paws in her ears and closed her eyes, waiting for Tuck to scream or panic and sink his claws in and for the deer to throw him off and make him scream even more. But unless she’d stuck her paws too far down her ears, none of this seemed to happen. She opened first one eye and then the other and pointed them both up at the deer’s antlers. Tuck was sitting up there, beaming.

‘Ginger!’ he yelled down when he could see she was looking. ‘This is brill! Look how high up I am. I can climb trees, look. It’s so, it’s so, it’s so cooooooooooool!’

Well, of course Ginger did a big gingery sigh and rolled her eyes, but when the deer asked her if she’d like a go too, she said, ‘Yeah, sure, why not. Nothing better to do. Might as well. Just to make Tuck feel more comfortable. S’pose.’

And within seconds there stood the deer with his huge and extravagant antlers each holding a hungry cat. ‘Would you like to go somewhere?’ he said.

‘Don’t suppose you know where there’s any rats?’ said Ginger.

‘Rats? No, dear. Lots of good grass I can take you to, though.’

‘Birds?’ said Ginger.

‘Ooh dear, you kitty-cats feeling peckish? I know just the place. Just over that hill in the distance there’s a small lake where the birds bathe and drink. If we leave now, we should arrive just in time for breakfast. By the way, my name’s Dozer. Shall we … ?’

As Dozer ambled through the trees and told Tuck and Ginger all about life in the forest, they both forgot their hunger completely. Neither of them had ever heard such stories, and although Ginger pretended she had, Tuck asked hundreds of questions about voles and weasels and ferns and burrows and pine cones and fireflies and bushfires, and oh, oh, oh, it sounded so exciting. It was only some hours later, when they had crossed over the hill and the sky had grown lighter and they could see the lake in the distance that either of them even thought about the birds they were going to have for breakfast.

‘What is a bird?’ said Tuck. ‘Is it a kind of flower?’

‘You’re funny,’ said Dozer.

‘Nah, just stupid,’ said Ginger.

‘I am not stupid,’ said Tuck. ‘I am not. You take that back.’

‘I tell you what,’ said Ginger. ‘You see how many of these funny animals you can catch when we get to the lake and I’ll not only take it back, I promise to never ever say it again. But you’ll have to catch at least four. And I warn you—you’ve got only once chance. One mistake and they’ll not come back.’

‘Are they rats?’ said Tuck, giggling slightly as Dozer tripped on a little stone and made his antlers wobble.

‘You’ll see,’ said Ginger. ‘Now shush. I want to get some shut-eye before we arrive.’ And with that she dropped into a deep doze, her paws tucked over her bellies and her chin deep in her chest. Dozer seemed to be sleeping too, as he walked, with his eyes closed and his breathing heavy. But Tuck was far too excited to sleep.

When they arrived at the lake, the two cats said goodbye to Dozer and thanked him for carrying them overnight. He asked if they were sure they wouldn’t like to stay in the forest, but even Tuck knew this wasn’t possible. They had to get back to Major’s farm as fast as possible to see what had become of him. So Dozer said a final goodbye and walked away through the trees, Tuck waving hard until long after he was out of sight. Then the two cats hid, and Ginger told Tuck all about birds.

Now, I know you might think it’s weird that Tuck doesn’t know about birds, but remember, he grew up in a cage and then went straight from there to an apartment. Until he and Ginger escaped, he knew about sky only because he’d heard people talk about it. Expecting Tuck to know about birds is like expecting you to know about bivalves. Exactly.

So Ginger told him all about them (birds, not bivalves). About their wings and how they could fly, about how feathery and flitty and flighty and fiendishly difficult to catch they were. She was so hungry she could barely bring herself to talk about how meaty and chewy and tasty-yummy they were too. But she forced herself whilst Tuck listened with eyes even wider than the last time he was wide-eyed (which wasn’t that long ago), and by the time the first few birds arrived at the stream, he was fully pumped for action. What could possibly go wrong?

A CHEEKY BIT

Parallels, parallels, will they never cease? From one hungry ginger cat desperately awaiting breakfast to another, this one slightly paler and locked in a witches’ apartment back in the city. Zoom out, pan left very fast, zoom in again, and there we are. Poor Major had had a terrible night of it. Like his long-lost love he was hungry and tired and desperate for his num-nums. The night before, Janice and Rodney had had a horrible fight.

‘What,’ said Rodney, as soon as Janice walked through the door, ‘is that?!’

He pointed with his fast-hooking nose at the cage she held in her hand.

‘It’s a cat,’ she said.

‘I know it’s a cat, you stupid witch,’ said Rodney. ‘But you were supposed to get a sleek, black, athletic cat. That … that … that thing is none of the above.’

Well, Janice was exhausted from being on her feet all the way up in the elevator and in no mood for being yelled at by Rodney. So she screamed back at him about there not bei

ng any black ones available as they were all sick, and she liked this one, and what had he ever done for her anyway, and didn’t she have a right to choose the cat she wanted, etcetera etcetera etceterargh.

While they were screaming and throwing insults at each other (there not being any china to throw, of course), Major crept between their warty legs and had a look at what was in the cage. Rodney had not been wrong. The cat that sat in there was not black at all. It seemed to be every other colour a cat can be except black. It had bits of brown, bits of tabby, bits of white, bits of tortoiseshell, all mixed up. It had very, very, very long hair and the hugest eyes you’ve ever seen. Its whiskers were so long they drooped under their own weight, and strangest of all, the cat in the cage had massively long hair protruding from its ears and even from between its toes.

‘Hello,’ said Major. ‘You’re not black.’

‘You’re not so ’ot yourself, fatboy,’ said the cat in the cage. ‘My name’s Minnie. What’s your name then, eh?’

‘Major,’ said Major.

‘Major?!’ said Minnie. ‘Major what? Major International Disaster Zone? Major Calamity? Major Health Warning? Major Look Major Stare Major Cut the Barber’s Hair? Ah ah ah ah ah ah.’

After a while Major realised the cat in the cage was laughing. She didn’t have the most pleasant of voices when she was speaking but this laugh, well. Most people laugh ‘Ha ha ha’, but Minnie most definitely laughed with an ‘Ah ah ah’ which was very annoying and surprisingly difficult to type. Now, as we have often said, Major was a dude. He was (apart from when grumpy) an easy-going cat. He was most definitely not a snob. At least not until now.

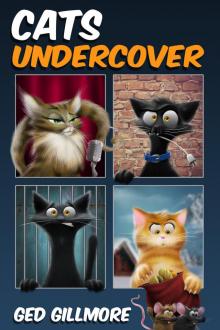

Cats Undercover

Cats Undercover Cats on the Run

Cats on the Run Cats On The Run (Tuck & Ginger Book 1)

Cats On The Run (Tuck & Ginger Book 1)